I just bought a couple of brand new copies of the tiny “Shambhala Pocket Classics” edition of the Dhammapada: The Sayings of The Buddha (translated by Thomas Byrom). This is the second book on Buddhism that I ever read, the first being Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind Beginner’s Mind, which my dad gave to me as a teenager. This edition of the Dhammapada has definitely been one of the most influential books to touch my life so far.

But this time around I noticed something interesting.

The fourth and fifth stanzas of the Dhammapada read as follows:

“Look how he abused me and beat me,

How he threw me down and robbed me.”

Abandon such thoughts and live in love.

In this world

Hate never dispelled hate.

Only love dispels hate.

This is the law,

Ancient and inexhaustible.

While a bit of nuance is certainly lost in translation, I think that this passage is massively intriguing and paradoxical, and that unpacking this has implications for human individual and social life that are worth exploring.

Love Can Dispel Hate, But Can It Dispel Sociopaths?

The notion that love (and only love) can dispel hate, is everywhere in so many different forms. It’s the Golden Rule. Or in this case, the Ancient Inexhaustible Law. But it is seldom practiced. Human relationship is riddled with conflict and trauma pretty much everywhere you look, and the Ancient Inexhaustible Law, while perhaps true, is not easy to follow. It might be the hardest thing for human beings to do, in part because it means going against our nature.

After all, this text is calling for love, not just in the face of insult, but of violence. If someone abuses you, and then beats you, and throws you down and robs you, then you should not invest your heart and mind in a narrative of wrongdoing and blame. So goes the argument. We are instead called to meet acts of overt violence with non-attachment and love, and to calm the tendency to resist or fight.

But why? When someone spews vitriolic poison your way, what’s your reaction? Love, or blame and defensiveness? What about unprovoked violence? Should you you not defend yourself? Get to safety and then find ways to hold them accountable? Punish them? What if we’re dealing with a sociopath? A totalitarian regime? This world is vast, after all, and filled with assholes.

In other words, from one perspective, the advice to love your enemies looks terrible and naïve. You’re not going to solve anything by loving some people, in fact you’re more likely to get yourself killed. Look at what happened with slavery in the Americas. Or First Nations all over the world during the colonial centuries in which we built our current civilization? If you have any sense, you’ll get some guns and hunker down for when the shit hits the fan. Love Jesus, and your neighbor, but not your enemy. Right?

But if loving your enemy and doing unto others is such bad advice, then why is the Golden Rule so Ancient and Inexhaustible? Why does an idea like love your enemies have any merit at all?

Love is Gnarlier Than Violence

I think part of the problem is that our common conception of love is far too simple and nice. In fact, love, when you get down to the part that counts, is gnarly. Love requires buckets of courage and work, and it requires having at heart the interests of the whole (the whole relationship, or family, or community) over the individual’s self interest. And in regards to the individual—real, courageous love favors honesty over harmony. Sometimes loving someone means going directly against what they want. Sometimes love requires that we face ourselves and each other in ways that are extremely uncomfortable, seeing and addressing what is difficult, and what wants to remain unseen. In order to really last in love, we have to confront the hidden—but very real—suffering and trauma that underwrites so much of our thoughts, words and actions.

This hidden suffering and trauma, as well as this potency of love, is part of the reason why relationships are so hard, and why science and the bureaucratic codification of retributive justice are inadequate for healing communities and restoring social order. And it’s part of the reason why dealing in love is more difficult, more courageous, more powerful, and more effective than dealing in revenge and violence.

Loving ones enemies, then, requires a recognition that enmity itself is taking place inside of us. It requires that we face into our own difficulty first, and model virtue and value outwardly as the actual, practical answer to our individual relationships and social problems writ large.

But it’s not as simple as all that, is it? Because unfortunately people everywhere like to fool themselves, and then they like to try to fool everyone else to protect themselves from their own bullshit. The Devil, as they say, is in the details.

And the Devil is really squirrelly too, so we have to be careful not to get lost in an echo-chamber of gaslighting and psycho-babble while we navigate the complexities of helping each other de-program ourselves from the indoctrination of late colonial industrialism. Staying focused on love—and learning the hard lessons thereof—is a good practice in these dire times, needless to say.

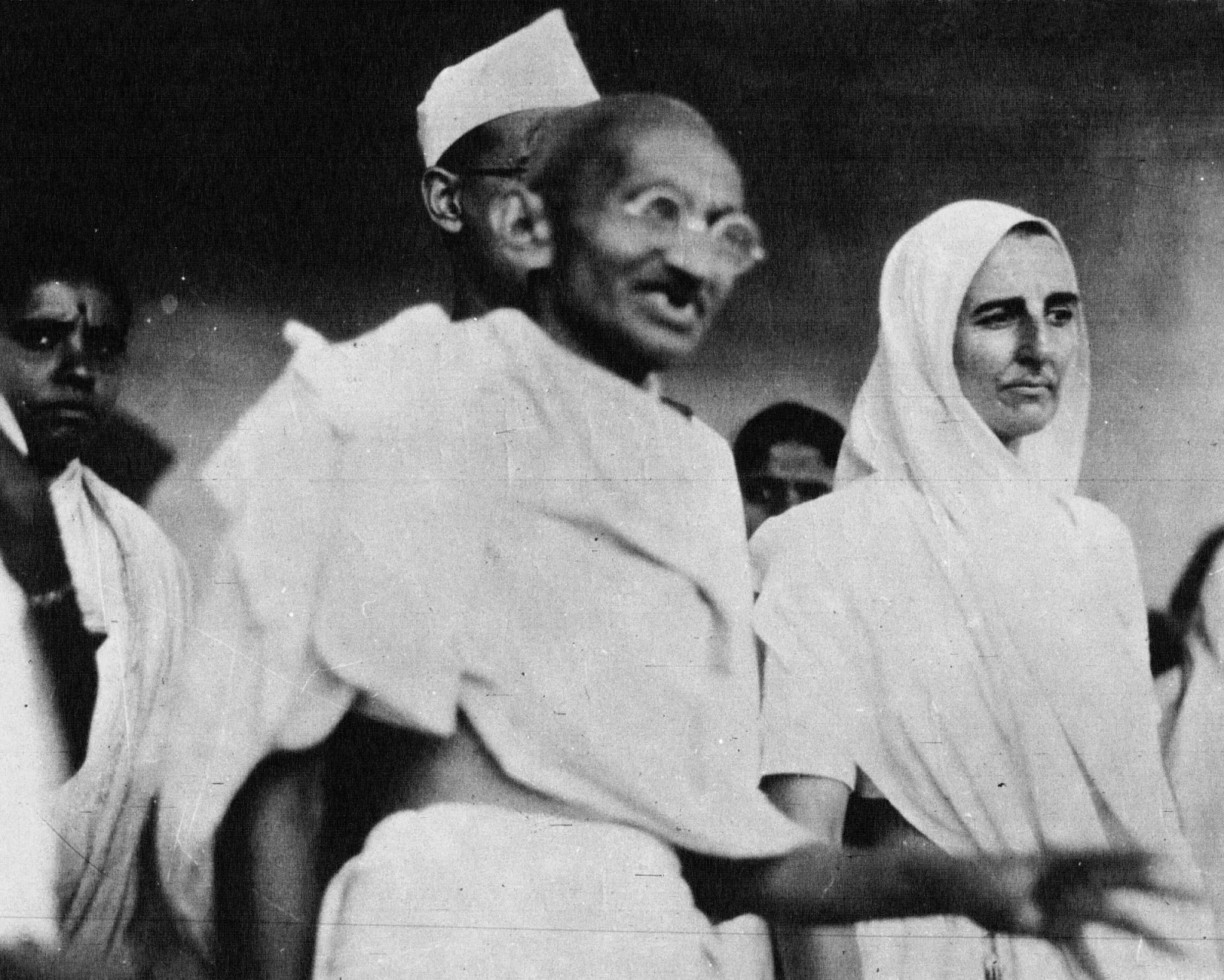

Satyagraha: Tough-Loving Your Oppressors While Committing Sexual Assault

At the social level, loving your enemies (or oppressors in this case) is most similar to the idea of satyagraha, a term for non-violent civil disobedience coined by Gandhi as he wore down British colonial rule by peaceful revolution, using strategic tea sessions, marches, philosophy, home-made clothes (boycott) and hunger strikes as his weapons of virtue.

Satyagraha is a powerful idea in part because it promises the possibility to interrupt the cycle of violence, by simply finding truth (satya) and standing firmly in it (graha). In other words, by grounding yourself in an ethical existence of integrity, and standing up for that even in the face of violence, you can reveal in stark relief the oppressive and violent constitution of those you oppose—even to themselves.

Satyagraha thus avoids a sentimental conception of goodness and truth, and instead advocates for taking a powerful stand, and holding fast to values and principles, come hell or high water. It is thus a way of absorbing violence with the strength and resilience of truth, while continuing to leave the door open for those that have been violent to join a strong culture of peace. This means finding a real moral high ground, and unwaveringly committing to it.

The problem is that truth is squirrellier than the Devil, and so it becomes easy to take a stand against cycles of violence that are obvious to you, even as you cause egregious harm and reinforce cycles of violence based on your ideas of truth. One great example of this is Gandhiji’s lesser-known misogynist exploits, the most notorious of which were perhaps his “tests of celibacy”. Following his wife’s death, Gandhi began taking naked young women into his bed, including his grandnieces who were then teenagers. He claimed this was to demonstrate to the world that his celibacy was pure and strong. But this was only the tip of the iceberg. Gandhi, it turns out, was as sex-crazed as any power-hungry man, and racked up a laundry list of weird sexual stories that make him ripe for a post-humous #metoo reality check (you can’t make this shit up).

So how do we deal with Gandhi now? How does his sexual perversion and repression echo in the hearts and minds of India and the world? How do we respond to this? With disbelief, throwing women further under the bus? Or disillusionment, sacking Gandhi’s humanity and nonviolence as a whole? Are our own hearts ready to hold the dichotomy and fallout of Gandhi as both a revolutionary and an abuser? How do we unravel violence from the human condition, when even those who make peace a matter of their life’s work, cannot help but perpetuate violence and trauma? Perhaps we should be asking: Can we love our friends, even when they become our enemies? And Can satyagraha work when the whole world is unwilling to even look at the truth?

The Inner Game of Loving Your Enemies

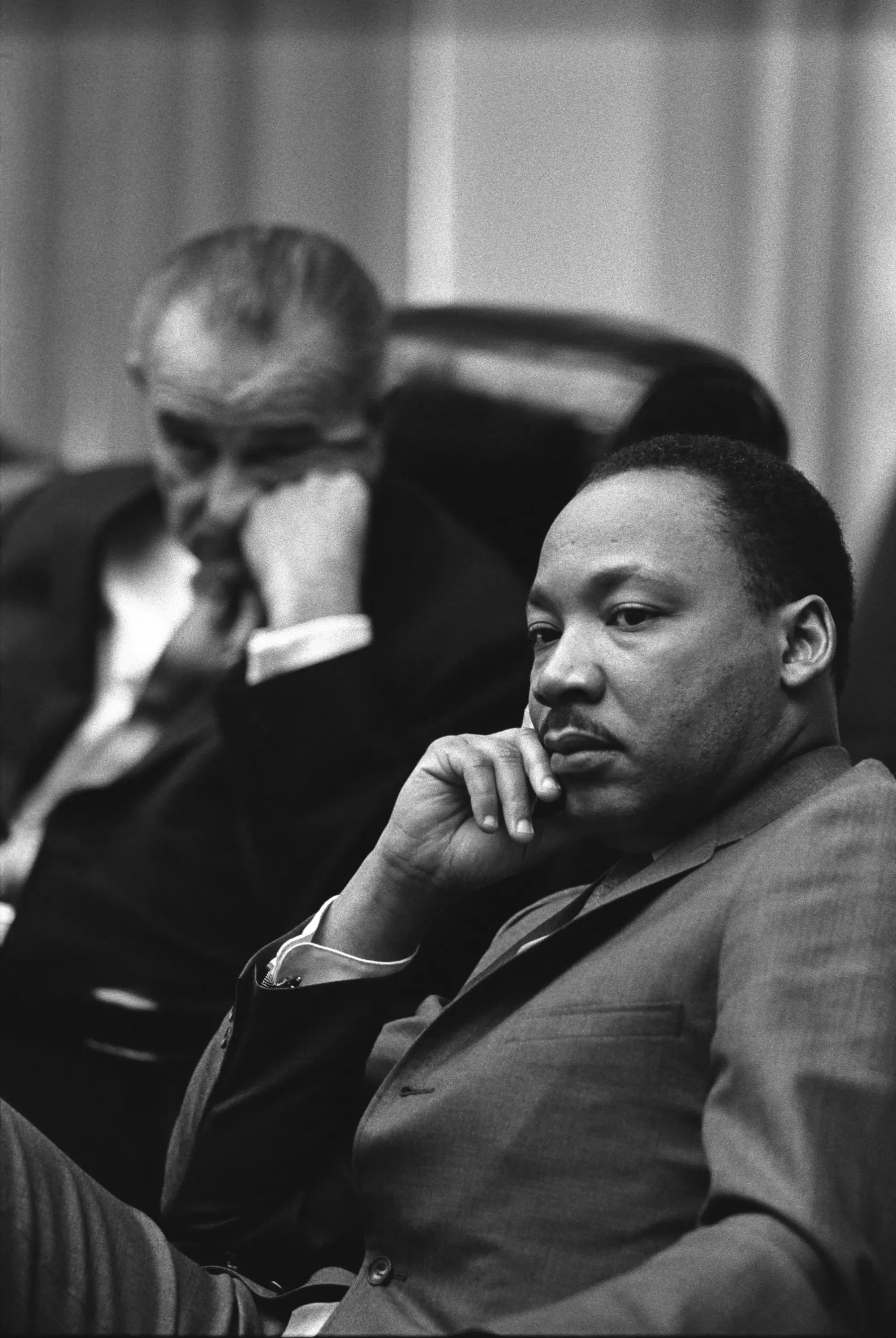

Regardless of this sordid history, Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence, along with Thoreau and Tolstoy, was heavily influential for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (is nothing sacred?) as he and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference set forth to transform the face of American democracy and eradicate the triple evils of racism, poverty and war through nonviolence. For Dr. King, loving one’s enemies was foundational to this project. He quotes from Saint Matthew in a 1957 Alabama sermon on the topic of loving your enemies:

“‘But I say unto you, love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them that despitefully use you’.”

Clearly, the great inexhaustible law, and the practice of nonviolence is not just referring to our our outward actions in the world but rather points directly to the way we are in our being, and the ways that we engage with our thoughts, and our consciousness. To actually answer this call means refusing to dehumanize others even as you are being dehumanized. It means recognizing that “within the best of us, there is some evil, and within the worst of us, there is some good.” (Ibid)

This recognition is crucial to the success of nonviolence, for it focuses both the generosity as well as the skepticism in both directions: inwardly as well as outwardly. Loving your oppressors, and loving yourself—even in the face of the ugly, complicated, multi-headed truth—requires getting face to face with the staggering risk and vulnerability of human life. If you believe in the humanity of the perpetrator, and you believe him capable of transformation, then you offer him a pathway to peace. And likewise if you believe in your own humanity and dignity, then avoiding and reducing harm to yourself is also paramount. So we must tread carefully on the razor’s edge between self-protection and our willingness to confront evil.

However, in order to do that skillfully, we also have to stay connected to our own fallibility. In order to even attempt the real ethical jiujitsu of satyagraha, we have to a) be willing to navigate the painful terrain of social violence (not that we have a choice), b) be willing to stand up for our right to be free from violence, c) be vigilant against our own confirmation bias, and d) be willing hear the impact of the social violences that we ourselves perpetuate. We have to do the long slow work of facing—and accepting, and de-programming ourselves from—the weird and deep ways that we ourselves cause harm in the world.

Of course it’s far too simple and easy to imagine a state of perfect freedom from fault, just as it’s too simple to elevate the practice of nonviolence to Godlike status of “truth”. We should be careful of the trap of advocating for some kind of “pure” peaceful inner state of tranquility that will allow us to defeat violence once and for all. This kind of end-game “thingification” of the world (and ourselves) has gotten us to where we are in the first place, imagining some perfect utopian future as a justification of our blind destruction of nature, the commons, and each other.

What this means is that we ought not take a firm stand in the truth, not if this means becoming hard of mind and stubborn of will and thereby causing more damage. We instead have to find out what it means to be truly committed to something even when embedded in a terrain that changes constantly. We have to become committed to befriending an enemy that’s not static and well-defined but rather messy, guaranteed to co-opt us unless we constantly re-check our assumptions, and come to terms with evermore uncertainty and risk. And we have to do this without losing our integrity and power. In fact, it seems to me that the will and power of integrity become stronger and more resilient when we are able to face and accept and ride the uncertainty of life. It is then that our will can get into alignment with the fabric of our nature, unleashing superpowers like patience, empathy, presence and unbridled creativity.

It strikes me that searching for and clinging to certainty is itself a form of violence, or at least one of the conditions that allows violence to arise. On the other hand a demonstrated commitment to learning from our faults and mistakes is a form of peacebuilding, and a prerequisite for social order. As Dr. King said, “this command is an absolute necessity for the survival of our civilization. Yes, it is love that will save our world and our civilization, love even for enemies.” These enemies, in other words, are within us as well.

The hard part is that in order to learn from our faults and mistakes, we have to first be willing to look at them, and this means facing our own blind-spots. It means foraging in the darkness of ourselves, and not turning away but instead saying “Okay, I can do this painful work of self-discovery.” It means that if we want to change the world, we have to train ourselves to see those parts that refuse to be seen, even at great risk to ourselves.

This means that we have to not only take punches, but that we have to stop the punching itself, all the while looking down at our own hands, to ensure that they’re not in fists. And if we can do this then the process of stopping violence will itself bear the mark of healing. It will look no different than coming to terms with the trauma that is everywhere in our lives and relationships, and eventually it will look like those who have benefitted from violence resourcing those who have taken the brunt of it. I am privileged to have witnessed this process with my own eyes and heart.

This process calls for trust, recognition, listening, and believing; and is built upon acts of generosity that reach across the chasms of hyper-individualism and the obsolete conceptions of siloed self-interest that have defined our economic and political institutions for too long.

This will look like understanding—at the institutional level—that belonging and accountability are the same, that it’s safe to understand and admit the harm you cause (but is it?), and that it’s safe to call someone to account (but is it!?). And while we’re a ways from reaching that stage in our history, some of us are called to do this most delicate and powerful work of building the real conditions for this kind of restorative justice to take place in our society.

Because as the long, slow arc of Western history inches its dinosauric ass up Ferguson’s Canfield Dr. in a police cruiser, it doesn’t lean towards justice quite quickly enough. And we who are invested in social change find the need to innovate, to imagine a new infrastructure of justice and accountability that is in line with the Ancient Inexhaustible Law, that is as agile as it is effective, and that helps to build the practices that make a living form of justice not only imaginable, but inevitable in a world that heretofore been accustomed to violence.